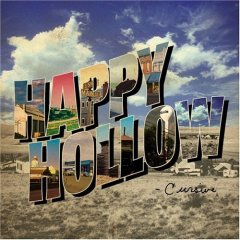

Happy Hollow is a fictional town set somewhere in the Midwest. It’s also the title and setting of the new Cursive album, and if you know anything about Cursive, you can probably guess that there aren’t too many folks within this small town that could actually be characterized as happy. If you have a son he’s off to war. If you have a job it’s killing you. If you know a priest he’s a closet homosexual. Or even better, he’s knocking up your daughter.

But through all of this misery, there is a sense of catharsis that comes along with Happy Hollow, or more accurately the specific catharsis that comes with giving up on god. In Happy Hollow, Cursive craft an album overflowing with these themes of divine longing and loss. With God always present in mind, but absent in physical presence, characters wander like lost children, tugging at coat sleeves, asking questions and truly searching, but ultimately being left to create their own truths.

Kicking off the record is “Opening the Hymnal/Babies”, a split track which serves as an introduction to the town before dissolving and eventually reemerging as the first true song on the album. Here singer/songwriter Tim Kasher sings to a child fresh out of the womb telling it — Such delusions we all struggle with/But the beautiful truth of it is/This is all we are/We simply exist –. It proves to be a sentiment that echoes throughout the remainder of the album.

Later “Retreat!” has an entire choir singing about God’s absence and the subsequent damage it has caused. — They check the shrine and the temple/but he wasn’t there/they checked the mosque and the chapel/no not there –. By the end of the song the only thing they have left to say is — Lord let us go — over, and over, and over again. And this is where the catharsis lies. The characters choose to abandon their God, as they have been abandoned. (And in gospel tinged chorus no less.) It truly feels an occasion to rejoice.

Of course Happy Hollow has its fair share of mortals dealing with other mortals. “Dorothy Dreams of Tornadoes” brings to mind a less personal version of the lyrics most anywhere on Domestica, while “Dorothy looks at 40” documents small town malaise. And although these songs both (Both!) successfully use the Dorothy archetype from “The Wizard of Oz” they still don’t hit with the same impact as the songs dealing with questions of divinity.

But beyond the new lyrical slant Cursive has also expanded musically. Cellist, Gretta Cohn, featured prominently on Cursive’s previous album The Ugly Organ has left and since been replaced by an entire horn section. With the brass accenting Cursive’s trademark, dissonant prettiness, they’ve honestly never sounded better. “Big Bang” rocks with a propulsive melody worthy of its title, while “Dorothy looks at 40” uses the lower horn section to push the verses forward with a galloping, rhythmic effect.

Later “So-So Gigolo” sleazes it up with a bass line that perfectly captures what you imagine when someone says the word gigolo, while somehow avoiding the obvious pitfalls here. Perhaps most impressively the 12th track “Into the fold” shows itself to be the most subtle and beautiful song Cursive has ever penned, all hushed vocals and soft organs, before a build that never really comes and is all the better for it.

Happy Hollow isn’t without its missteps however. “Flag and Family” although interesting musically, feels cheap lyrically, referring to off stage (so to speak) characters as –Bigots and fanatics –. Another track has Tim yelling — This city’s killing us– and even if that is true in the context of the record, it all just feels a little tired. That said however, Cursive rarely fail in such a way. In fact, most of the time they get away with a lot more than I would have thought possible.

I mean, come on! Who titles a song “So-So Gigolo” and gets away with not playing it up for laughs? Instead they throw out references to Greek mythology like — Small town Adonis/hits the metropolis/brought down to his knees –. These lines should not work, with all of their double entendre and unfunny male prostitution, but within the confines of the song, they do. It’s only every so often that the scale tips a little too far this way or that. An odd rhyme here, a graceless sexual allusion there. But in a production such as this, complete with a final reprise documenting all that has occurred in a table of contents style sing-along, there are bound to a few occasional lows, along with all these remarkable highs.